Empathy, Apathy, and the Politics of Caring

- Swasti Chaudhary

- Sep 3, 2025

- 3 min read

As several workers remain gathered outside Gate 1 of Ashoka University to have their demands of fair pay, clear increments, and the reinstatement of wrongfully fired employees heard, the student body’s response has been fractured and largely lacking a sense of collective urgency. My intention with this article is not to point fingers and blindly criticise this reality, but rather to appeal to a student body that I know firsthand is capable of the introspection required to make change. The contrast between the students sitting outside in unity with the housekeeping staff and the hundreds of students lining up to enter the campus after their first Thursday night out is a gruesome symptom of an ailment that can only be described as apathy.

This apathy is not just a failure of empathy; it is also a failure of judgment. Collective urgency only seems to manifest for matters that adversely affect leisure experiences on campus. The inconvenience of putting bags through scanners or a slightly more policed Thursday night experience takes precedence over systemic problems that adversely affect the workers’ livelihoods. If the protest against baggage scanners taught us anything, it is that students are capable of shedding this apathy. For a student body that was able to put individual politics aside to scrutinise and challenge excessive surveillance, the workers’ strike emerging from years of oppressive treatment is yet to be met with the same outrage.

Another manifestation of this apathy is the lack of ideological diversity in the students sitting at Gate 1 when compared to the students who protested against the scanners at Gate 2 last semester. Students from left, right, and centrist leanings united at the latter protest, mobilising based on concerns around privacy and surveillance. That convergence was likely enabled by the issue’s more immediate, personal impact on every student on campus. In contrast, the ongoing worker’s strike has not generated the same cross-spectrum engagement, with participation largely confined to students already associated with progressive or leftist politics. The problems that the workers have been facing call for solidarity that looks past petty discussions of left-right politics. It would not be an exaggeration in the slightest to deem the issue of workers’ rights as one that warrants unwavering support. Yet, this divide persists and shows how certain political positions can make apathy feel acceptable– left-leaning students tend to mobilise, while many centrist or right-leaning students dismiss such struggles as overly political or irrelevant. In doing so, apathy is framed as an acceptable and neutral choice rather than a withdrawal from collective student responsibility.

The questions that glare at us are: does the average student not feel compelled to inquire why, despite the infamously high fees, the workers of Ashoka are not paid a respectable wage? Can a university that offers paid positions to student Teaching Assistants and Resident Assistants not accommodate a 5,000 rupees raise for workers who have been the backbone of the institution for several years? Is the student body not capable of seeing issues that do not directly affect them, as real problems with lives and freedom at stake? Or are these problems condemned to remain abstract issues of labour rights, speaking about which helps account for a class participation grade?

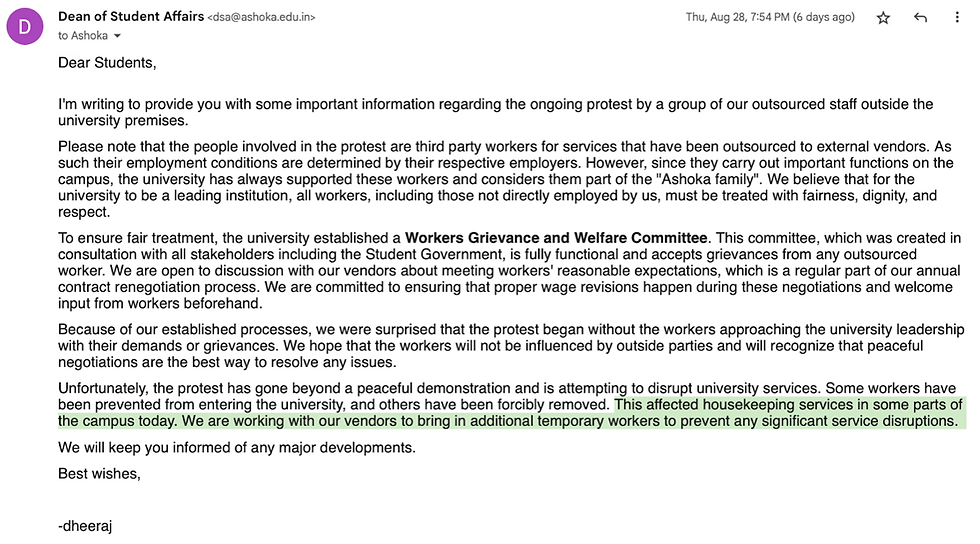

Universities like Ashoka cannot claim to nurture global citizens while ignoring the rights of the very people who keep the institution running. Students at Ashoka cannot claim to be engaged global citizens without reserving a rightful place for labour rights in the larger human rights discourse. One of the only pieces of communication we have received from the Dean of Student Affairs has been an email that criticised how the protest affected housekeeping services on campus—how much does the workers’ absence have to be felt for their demands to be met?

If there is anything the past has shown us, it is that Ashoka students can mobilise, and when they do, their collective voice carries weight. The urgency felt during the protests against scanners proved that students are capable of transcending ideological divides to demand justice. That same spirit is needed now.

(Edited by Avika Mantri and Madiha Tariq)

Comments